High Production Forestry in the Ingram River Wilderness Area

As your Municipal Councillor, I frequently receive inquiries and concerns regarding the future of the Ingram River Wilderness Area. While these are provincial Crown lands managed by the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables (DNRR), the decisions made there have a direct impact on our local communities—affecting everything from wildfire safety to our local recreation and tourism economy. This post is intended to provide a clear, evidence-based overview of the current situation on the ground. I've done my very best to cite everything in this blog, and I would encourage residents to read beyond what it is written here. My goal in writing this post is to help residents to understand the situation and concerns, the ecological significance of this land, and why so many in our community are calling for its protection.

Historical Context:

The contemporary struggle over the management of the Ingram River watershed is rooted in a pivotal moment of Nova Scotian economic history: the 2012 insolvency of the Bowater Mersey Paper Company. This collapse represented a paradigm shift for the western and central regions of the province, as it effectively terminated decades of private industrial control over a vast forest landbase.1 In response to this crisis, a broad coalition of citizens, environmental organizations, and community groups initiated the "Buy Back the Mersey" campaign, advocating for the provincial government to reacquire these lands as a public asset.1 The successful campaign resulted in the Province of Nova Scotia purchasing nearly all the former Bowater Mersey holdings, with the explicit policy objective of putting these lands "back in the hands of Nova Scotians" for multi-value management.1

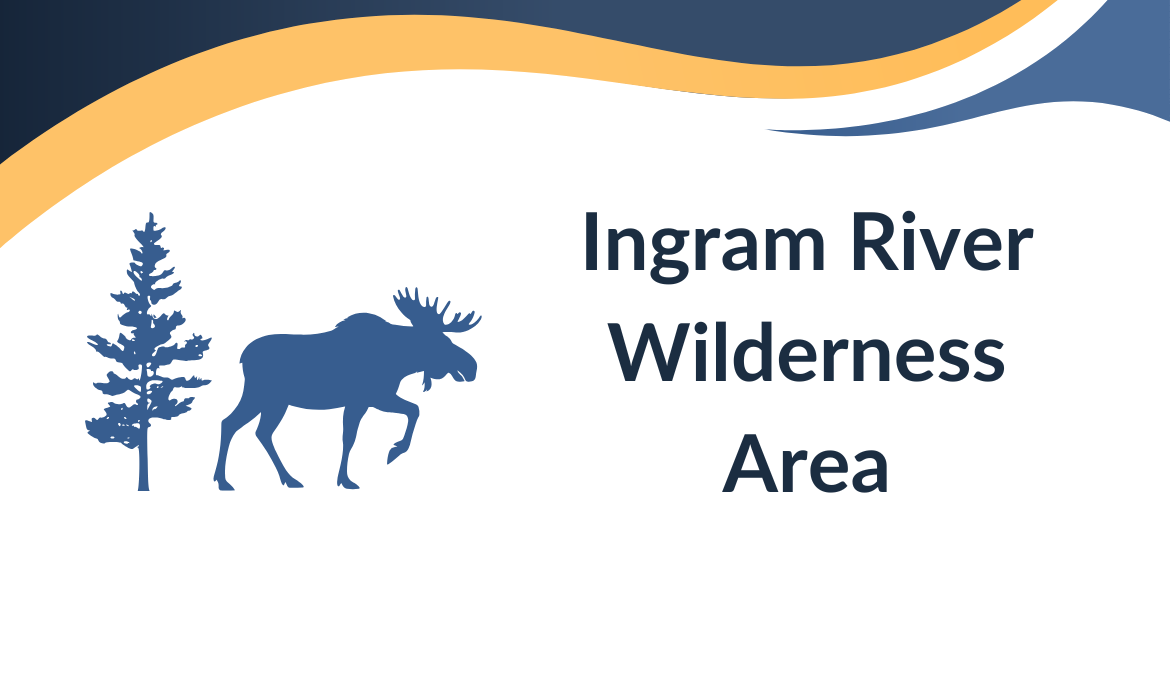

The St. Margaret’s Bay Stewardship Association (SMBSA) emerged as a central voice in this transition, proposing that a significant portion of these lands—specifically within the Ingram River and Indian River watersheds—be designated as a protected Wilderness Area.1 This proposal was not merely a reaction to industrial logging but a forward-looking vision for ecological renewal and community economic diversification. The proposed Ingram River Wilderness Area (IRWA) was designed to protect just under 11,000 hectares of publicly owned forests and waterways that drain into St. Margaret’s Bay.2 These lands encompass dozens of undeveloped lakes and brooks that connect the remote interior of the watershed to the Atlantic Ocean, providing a rare opportunity for landscape-level connectivity in Halifax Regional Municipality.2

Despite the initial optimism surrounding the public reacquisition, the management trajectory of the Ingram River lands remained contested. The SMBSA felt a sense of "big letdown" as successive governments appeared to default to traditional industrial exploitation models rather than embracing the "light-touch" community forest proposal put forward by local stakeholders.1 While the government designated the 3,850-hectare Island Lake Wilderness Area in 2021—effectively protecting about 25 to 30 percent of the original vision—the remaining 75 percent remained under a management regime that prioritized industrial fiber extraction.3 In 2025, the province doubled the area designated for HPF within the IRWA to approximately 164 hectares (~405 acres).4 This expansion puts the oldest documented forest in the Maritimes and core moose habitat at immediate risk of industrial "final felling".4

High Production Forestry: A Primer

The current forest policy in Nova Scotia is governed by the Triad Model of ecological forestry, a framework introduced by Professor William Lahey in his 2018 Independent Review of Forest Practices.5 The triad seeks to mitigate the historical conflict between ecological integrity and economic productivity by partitioning the 1.8 million hectares of Crown land into three distinct management zones: the Conservation Zone, the Ecological Matrix, and the High Production Forest Zone.6

Allocation and Objectives of the Triad System

| Management Zone | Primary Goal | Silvicultural Approach | Area % (Crown) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservation Zone | Biodiversity and natural processes | No resource extraction; emphasis on old growth and SAR habitat | ~35% (current) 7 |

| Ecological Matrix | Multi-value stewardship | Lower-intensity multi-aged management (irregular shelterwood) | ~55% 6 |

| High Production (HPF) | Maximum timber yield | Intensive "agricultural" model; clearcutting and plantations | Max 10% 8 |

Comparison of Management Paradigms:

| Feature | Traditional/Natural Forestry | High Production Forestry (HPF) |

|---|---|---|

| Regeneration | Natural seeding | Planting improved stock (Spruce) |

| Harvest Rotation | 60 to 90 Years | 25 to 40 Years |

| Competition | Natural succession | Chemical (Herbicide) suppression |

| Source Citation | 9 | 7 |

The implementation of HPF involves several critical silvicultural interventions. Following a "final felling" (clearcut), the site is often mechanically prepared to facilitate the planting of high-quality, fast-growing spruce seedlings.7 To ensure these seedlings reach maturity without being outcompeted by native hardwoods or shrubs, the government authorizes the application of glyphosate-based herbicides.3 This process is intended to produce a high-value crop of sawlogs in nearly half the time required by natural processes.7

The theoretical underpinning of the triad system is that by intensifying yields in the HPF zone, the province can maintain a viable forestry sector while allowing the Ecological Matrix to prioritize biodiversity preservation.8 However, application of these zones has become the primary source of conflict within the Ingram River area. Critics argue that the DNRR has failed to uphold Lahey’s principle that "protecting and enhancing ecosystems and biodiversity" must be the priority.3 The fast-tracking of HPF designations suggests a prioritization of industrial fiber over the legislative goal of protecting 20 percent of provincial lands by 2030,10 and lack of consideration for the unique ecological value Ingram River represents.

Ecological Significance of The Ingram River Wilderness Area:

| Ecological Metric | Value / Count | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Total Area Proposed | ~11,000 Hectares | 11 |

| Oldest Documented Tree | 535-year-old Hemlock | 12 |

| Species at Risk (SAR) | 17 Documented Species | 3 |

| Mainland Moose Status | Legally Designated Core Habitat | 13 |

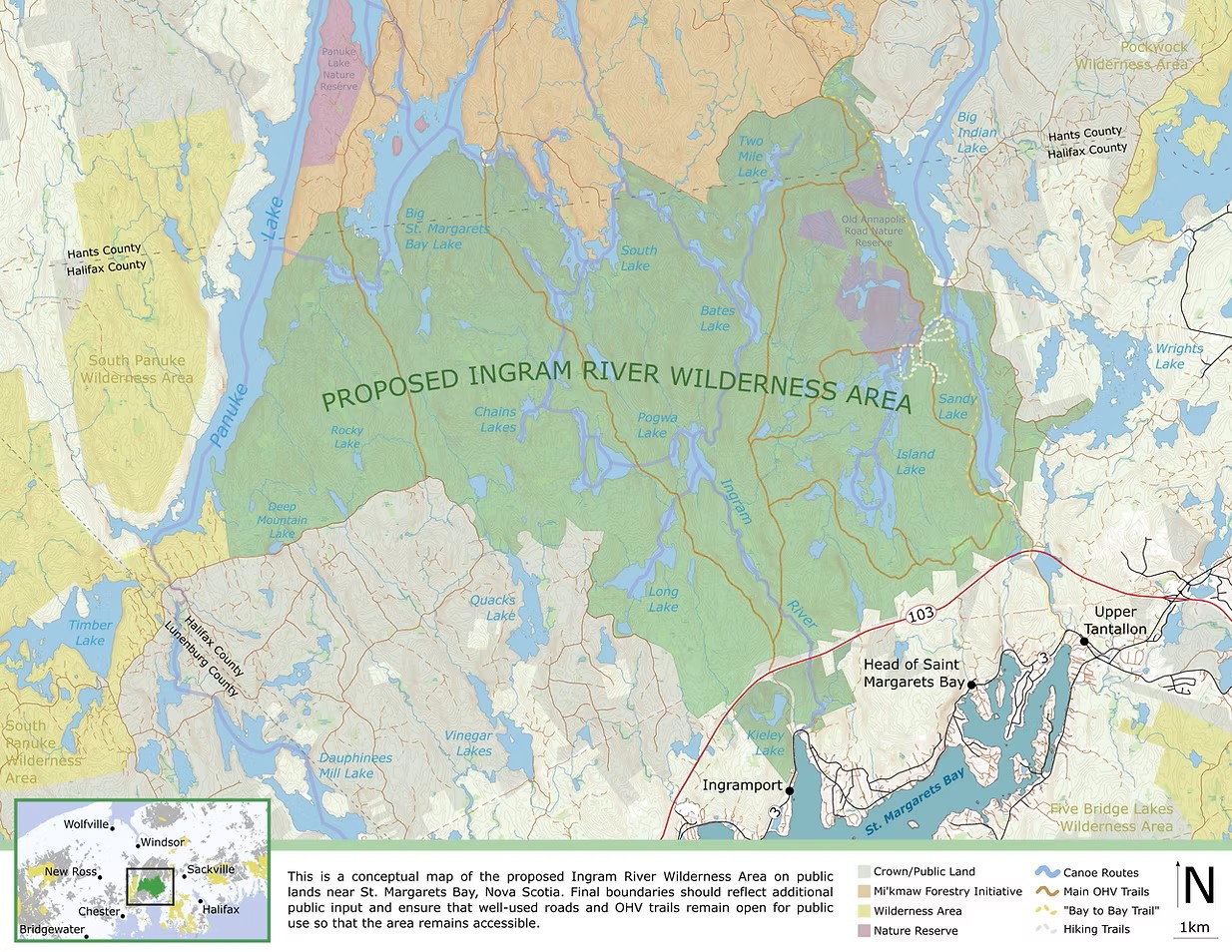

The Ingram River Wilderness Area is characterized by its high concentration of ecological "anchors".10 Foremost among these is the presence of the oldest documented forest in the Maritime provinces, 12 , and its ecological value as a corridor and core habitat for Mainland Moose. Core habitat for Mainland Moose is defined as land "essential for the long-term survival and recovery" of the species.3 The fragmentation of this habitat through intensive clearcutting is viewed as a primary barrier to recovery, yet the government has increasingly slated these habitats for HPF development.4

Prioritizing HPF in the Inrgam Wilderness area appears to contravene existing policy, where it is stated, "It will not be done on Crown lands that include or are near parks and protected areas, old growth forests, sensitive habitats, tolerant hardwood or pine forests, special wildlife management zones, buffers along watercourses or areas with high Indigenous cultural value."17

Economic Importance:

The debate over the Ingram River watershed is often framed as a choice between "jobs and the environment," yet a local analysis of the economic reality reveals a more complex relationship between timber extraction and the local economy. Many local and small businesses in St. Margaret's Bay area identify the significant current and future potential the IRWA has in the "New Economy," which includes ecotourism, outdoor recreation, and guiding, camping, and a valued revenue stream in the community currently. The Tourism Industry Association of Nova Scotia (TIANS) supports the IRWA designation precisely because it preserves the "extraordinary natural amenities" that sustain the $1.7 billion tourism sector. Beyond that, the prime location within HRM gives easy access to nature for tourists and residents alike.

Wildfire Risk and Climate Resilience

A secondary, yet critical, impact of High Production Forestry is its effect on landscape-level wildfire risk. Native Acadian forests are naturally more fire-resistant than coniferous plantations.14 The HPF model prioritizes spruce monocultures and uses herbicides to eliminate fire-resistant hardwoods, resulting in a landscape dominated by highly flammable conifers prone to "candling".15

In an era of increasing extreme weather and drought, the decision to convert the Ingram River watershed into an intensive softwood plantation may heighten the risk to nearby communities in Tantallon and across the St. Margaret’s Bay region. This remains a primary concern, in light of the 2023 Tantallon wildfires and the 2025 wildfire at Big Indian Lake in the immediate vicinity.

Health Risks:

The use of chemical spraying remains a significant concern for residents in the area. Glyphosate is classified as a "probable carcinogen" by the World Health Organization.16 Research indicates it can accumulate in forest plants like wild berries for a decade or more.14 Furthermore, these chemicals are highly toxic to "keystone" forest organisms like amphibians, with toxicity increasing in our naturally acidic Nova Scotian waterways.14 Concerns also remain about well contamination from runoff by local residents, and note the number of ponds, streams and lakes in close proximity to proposed HPF sites. Related, other sources note the flood control and carbon sequestration benefits.18

The Ingram River Wilderness Area is also viewed by residents as their 'really big back yard'. Many residents in St. Margaret's Bay, HRM and beyond utilize the area for hiking, paddling, fishing, ATV/OHV usage on designated routes, and all forms of outdoor recreation for their physical and mental health. Far from being an unused or underutilized plot of land, the IRWA is enjoyed by many.

Map of club trails: ATV NS

Erosion of Public Trust:

The doubling of HPF area to 164 hectares in 2025 has been viewed as a betrayal of public engagement processes.10 A primary grievance of the SMBSA and the Healthy Forest Coalition is the government’s 2021 commitment that areas not protected under the Island Lake Wilderness Area would either be added to the Conservation Zone in the future or managed under the Ecological Matrix leg of the triad.6

In 2021, a provincial news release quoted, "We are delighted to see the proposed Ingram River wilderness area finally advancing to public consultations for an eventual designation of a significant large wilderness area in the St. Margarets Bay district. This district has traditionally been underrepresented in Nova Scotia’s Parks and Protected Areas Network, so this will bring the area up to par with other districts in the province. The area has tremendous recreation and conservation values, including pockets of old growth forests, which are provincially rare and in need of protection.”19 The subsequent announcement that these lands would instead be targeted for High Production Forestry—effectively clearcutting—has been viewed as a betrayal of public engagement processes.6

The lack of transparency is further exacerbated by the Harvest Plan Map Viewer (HPMV) system. While the government claims this system allows for robust public input, advocates note that many long-term development plans are not archived or easily searchable, and "TBD" (To Be Determined) is often listed for prescription types, preventing meaningful public oversight.21 This "opaque" process is a significant barrier to the community-based stewardship envisioned after the Bowater Mersey buy-back.

The role of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests has been instrumental in revealing internal contradictions. Linda Pannozzo’s reporting for the Quaking Swamp Journal revealed that while the government publicly downplayed the ecological sensitivity of harvesting sites, internal documents acknowledged that the Ingram River forests were "crucial" for the survival of the endangered Mainland Moose.20 Furthermore, retired government insiders have called for a "seismic shift in the status quo,"20 describing a management culture that remains beholden to industrial consortiums like WestFor, whose priorities are seen as overriding community-led conservation initiatives.

Sources

- Our Campaign | Ingram River Wilderness Area

- Protect the Ingram River Wilderness Area

- Ecology Action Centre - Statement on Clearcutting

- NS Forest Matters - Proposed IRWA & Internal Documents

- Nova Scotia's Triad Model

- Triad: A New Vision for Nova Scotia Forests (PDF)

- NS News Release - HPF Zone in Place

- HPF Phase 2 Guidance Document

- High Production Forestry - Phase 1 Report

- NS Forest Matters - Targeted for Perpetual Clearcutting

- Protect the Ingram: Area Overview

- CBC - 532-year-old Hemlock Record

- Recovery Plan for the Mainland Moose (PDF)

- EAC - Position on Herbicides and Fire Resistance

- Reddit Halifax - Discussion on Fire-Prone Forest

- EWG - WHO Labels Glyphosate Probable Carcinogen

- High Production Forest Zone in Place

- Economic Benefits - Ingram River Wilderness Area

- New Proposed Protected Area Near St. Margarets Bay Added to Consultation

- A Trust Betrayed: FOI reveals Ingram River forests "crucial" for endangered moose; and retired government insider calls for a "seismic shift in the status quo"

- CBC InfoAM interviews on Logging in Citizen-Proposed Protected Areas